Complaint handling casebook: Resolving issues informally

Date posted:

Foreword

My office is frequently in the news for its big investigations, often about some systemic failing in public administration that needs to be fixed. But the work of my office is infinitely greater than the headlines it generates. Every working day, staff in my Complaints and Conciliation teams are resolving people’s complaints.

There are many thousands of them, every year. Most people who complain to us are not looking for an Ombudsman investigation, they are looking for a quick or meaningful solution. They have a problem, and they want it fixed.

This report describes how my office resolves complaints without formally investigating. Of course, not all complaints can be resolved informally, or to a complainant’s satisfaction. But many can be, with a phone call or a few emails to explain the situation. Since 2020 we have also had the power to conciliate complaints, and this report shows how both parties benefit from this process when they are face-to-face and led by a qualified conciliator.

Our conciliation case examples demonstrate what can be achieved by this new function. It is a particularly useful tool when there is an ongoing relationship between the complainant and an agency, such as a tenant in public housing, and there have been multiple ongoing complaints that could not be resolved. Bringing parties together can achieve tangible and lasting results to some intractable problems.

The cases in this report illustrate what can be achieved when complainants have a potentially legitimate grievance and when, prompted by the Ombudsman, agencies are willing to reconsider decisions. The cases describe a restless city-dweller getting his post-lockdown travel voucher after initially being denied; a pensioner in public housing getting her leaky roof fixed; the owner of a hybrid vehicle getting a discount after initially being denied by VicRoads because of a mistake.

Prisons are the agencies people most frequently complained about to the Ombudsman, and these complaints too can sometimes be fixed with a phone call. In one case, the dignity of a menstruating prisoner was not respected, but due to our intervention, policies changed to stop such disrespect happening again.

Local councils also feature heavily in Ombudsman complaints, and fixing a complaint for one person can often fix a problem for many. A new homeowner complained about being charged an infrastructure levy – which should have been paid by the developer – and our intervention resulted in the levy being waived not only for them but for 13 others. And a parking infringement imposed on a driver due to a confusing sign was not only revoked, the sign was replaced so others would not have the same problem.

I thank the agencies in this report, and the many others we deal with daily, for their willingness to engage informally with my office to resolve complaints.

These stories demonstrate that although we hold powers similar to a Royal Commission, the nudge of the Ombudsman’s elbow is often the only power we need.

Deborah Glass

Ombudsman

Our role in resolving complaints

One of the main roles of the Victorian Ombudsman under the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic) is resolving complaints we receive from the public about the actions and decisions of public organisations (‘authorities’).

These authorities include Victorian government departments, local councils, statutory bodies and often, publicly-funded bodies. There are a few exceptions, for example, we generally cannot consider complaints about police, employment issues, freedom of information requests or court decisions.

We aim to assess and resolve complaints quickly, achieve fair and reasonable outcomes and improve public administration.

Most of the complaints we receive can be resolved ‘informally’ by telephone or through online communication without needing a formal investigation. In negotiation with authorities, we can recommend certain outcomes or propose specific remedies. There are many ways to informally resolve complaints. Authorities may:

- offer us a response or outcome to a complaint

- give reasons for its decision

- apologise or admit to a mistake

- agree to consider a matter further

- provide a refund or waiver of fees and fines

- offer a payment

- review or change a policy or procedure

- fix the problem raised

- implement further training for staff

- reach an agreement with the complainant.

The process of engaging with a complaint may also assist an authority to fix systemic issues and reduce similar complaints in the future.

Since 2022 we have been using new powers under the Ombudsman Act to resolve complaints informally using conciliation. We use conciliation where the best outcome is achieved by getting parties together to find solutions, in a supported and structured setting. Led by our conciliators, the conciliation process is voluntary for authorities and complainants.

In some cases it is not appropriate to attempt to informally resolve a complaint. Some cases are too complex or require the use of the Ombudsman’s coercive powers to investigate. The Ombudsman may also decide not to deal with a complaint further. This happens when we find, for example, that an authority’s actions or decisions were not unreasonable, or when we cannot achieve a practical solution to the situation.

The Ombudsman has received an average of 21,665 complaints each year over the past five years. Most are resolved informally.

Most commonly, complaints are informally resolved by us facilitating communication between the complainant and the authority. This reflects the fact that authorities failing to communicate clearly or promptly are amongst the most common complaints we receive.

The second most common informal resolution is the complaint being fixed by the authority, followed by authorities explaining their reasoning behind their decision.

The cases in this report demonstrate the various outcomes the Ombudsman can achieve. We have grouped these examples by outcomes. You will see cases where an authority:

- resolves a complaint by taking direct action about the problem

- provides a refund or makes a payment

- reflects on and changes its policies or decisions

- agrees to meet face-to-face with the complainant and participate in a conciliation to resolve the complaint.

The examples in this report are all real cases. To protect people’s privacy, we have used pseudonyms.

Resolving complaints through making enquiries

We can make enquiries with an authority under section 13A of the Ombudsman Act. This allows us to seek further information about the complaint from the authority. Under the Ombudsman Act, the authority must assist the Ombudsman in the conduct of an enquiry.

Often authorities make unfair decisions because they follow processes without considering the circumstances of the case. In many cases, our enquiries prompt authorities to reflect on the circumstances of the complainant and use their discretion to make a different decision.

Prompting authorities to act

People often complain to the Ombudsman about an authority not responding to their request. We can help resolve these complaints by prompting the authority to engage and answer the request.

It is important for an authority to acknowledge its mistakes. Sometimes the Ombudsman needs to step in to highlight the mistake, and the steps an authority could take to resolve it, as well as apologising.

Poor communication from authorities when dealing with issues or responding to complaints can further compound the problem. This is a frequently complained about issue. Authorities may fail to acknowledge a complaint, to answer in a reasonable timeframe or to respond in a way that addresses the issue raised. Enabling a complainant to ‘feel heard’ is a key feature of good complaint handling.

The following case studies highlight the different ways the Ombudsman works with authorities to prompt them to take direct action about the issue. Communication is one of the most important factors, as is remembering each complaint must be dealt with on its own merits. We highlight below where authorities have:

- offered a better explanation

- provided the reasoning behind the decision

- apologised for the mistake

- fixed the issue.

Case study 1 – Travel Voucher application dismissed by Department

When Covid-19 lockdown restrictions ended, Business Victoria launched the Victorian Travel Voucher Scheme which offered people a $200 reimbursement for travel within Victoria.

The scheme was designed to kick-start travel in Victoria again and was the perfect excuse for Milos to explore Victoria after months of being confined to his home.

Milos looked at the criteria of the scheme on Business Victoria’s website. He noted the dates that the travel vouchers covered and designed an itinerary for his excursions across the State.

When he returned and lodged his travel receipts with Business Victoria, he was denied a reimbursement. Milos lodged a complaint shortly thereafter.

Milos was told he was not eligible for a rebate because he travelled on dates that were not covered by the scheme. Milos referred to the Frequently Asked Questions page of the Business Victoria website, which stated the approved travel dates, only to be told by the Department that these dates were in fact wrong.

Business Victoria had become aware the dates on its website were wrong three days before Milos contacted them and corrected the error. However, they still they denied Milos his reimbursement.

Believing this decision to be unfair, Milos contacted the Ombudsman.

After we made enquiries, Business Victoria accepted it made an error and reviewed its decision to reimburse Milos.

Business Victoria also agreed to honour the dates initially displayed on their website for applicants who could provide evidence that they travelled during that period.

Case study 2 – Delayed response to pensioner with leaky roof

Public housing resident Ethel, who was 92 years old and legally blind, was struggling to keep up with maintaining her home.

Her roof had been leaking for some time. The Department of Families, Fairness and Housing had tried to repair the roof more than once, but Ethel would still find her floors wet after a sudden downpour.

Ethel’s son reached out to the Ombudsman for assistance, explaining that the issue had remained unresolved for six months.

Following our involvement, Ethel received an apology from the Department. The Department also planned additional works on Ethel’s home including replacing downpipes and spouting in the affected area, completing the ceiling repairs, and repainting Ethel’s dining area.

What can we learn?

It is essential to good complaint handling that the remedy proposed by the authority try to address the cause of the complaint, not just the symptoms around the issue. In both case studies, the initial response from the authority did not resolve the problem at the heart of the complaint. In the Business Victoria case, amending the incorrect information on the website did not address the fact that the complainant wasn’t being reimbursed.

When initially assessing a complaint, authorities should also consider the seriousness and complexity of the complaint and whether it raises issues which may affect the broader community.

Ultimately, following our enquiries, both authorities rethought their decision and offered further remedies which informally resolved the issues and may have helped many others.

Case study 3 – Delay with compliance certification for new home

After years of planning, the final touches on Reiko’s dream home were finally being put in place. However, before he could move in, Reiko’s surveyor needed the builder to issue a compliance certificate.

As Reiko’s builder failed to issue the certificate for some time, Reiko lodged a complaint with the Victorian Building Authority (‘VBA’).

After waiting six weeks for a response, Reiko was frustrated to learn that a staffing issue meant that the VBA had still not assigned anyone to look into his case:

It has been more than a month since I lodged my complaint, and the VBA is yet to even appoint a contact person to look at it. Who knows how much longer it may be before action is taken.

Reiko

Reiko turned to the Ombudsman and we made enquiries. Within two days of contacting us, Reiko received a response from the VBA and an outcome letter the following week.

The VBA’s response allowed Reiko to resolve the issue with his builder directly and the compliance certificate was issued shortly after.

Case study 4 – Hold up on Working With Children Check for tour guide

Since retiring from his professional career, Harold has kept his mind and body active with part-time work as a historic tour guide.

As his tours often involve children, a Working with Children Check was required. Harold attempted to renew his certificate online but was having trouble navigating the digital platform.

Complicating the issue further, the Working With Children Check service centre was not taking calls so Harold could not resolve the matter over the phone – as was his preference.

Look I’m stuck, I mean there's something wrong with the system there. I mean, for them to have a help number advertised on their website saying, ‘contact us this way’, and when you do it says, ‘we’re not doing anything’ and hangs up on you. It’s not really good enough.

Harold

Unable to work without his certificate, Harold complained to the Ombudsman.

Following our enquiries, the Working With Children Check unit of the Department of Justice and Community Safety quickly contacted Harold by phone, stepped him through the process and helped him lodge his renewal application.

What can we learn?

Every year we receive a large number of complaints about delays. Our Complaints: Good Practice Guide for Public Sector Agencies and the Australian Standard Guidelines for complaint management in organisations (10002:2022) both discuss the benefits of addressing complaints promptly. The Ombudsman expects agencies to respond to straightforward complaints within 28 days. In the VBA case study, the delay in handling the complaint had a flow on effect for the complainant, preventing him from moving into his new home.

Authorities also need to recognise not everyone can make a complaint in writing. Complaint pathways need to be accessible, including for those who have a disability or have cultural or language challenges. In the Working with Children Check case a lack of complaint options meant the complainant was unable to seek the help they needed.

Having a clear explanation of the complaint handling process, including how a complaint will be dealt with and when the complainant can expect a response, might have alleviated some of the frustration in these cases. In both cases the Ombudsman facilitated communication between the authority and the complainant. These cases highlight the impact delays and communication accessibility can have and how clear and open communication can quickly and informally resolve complaints.

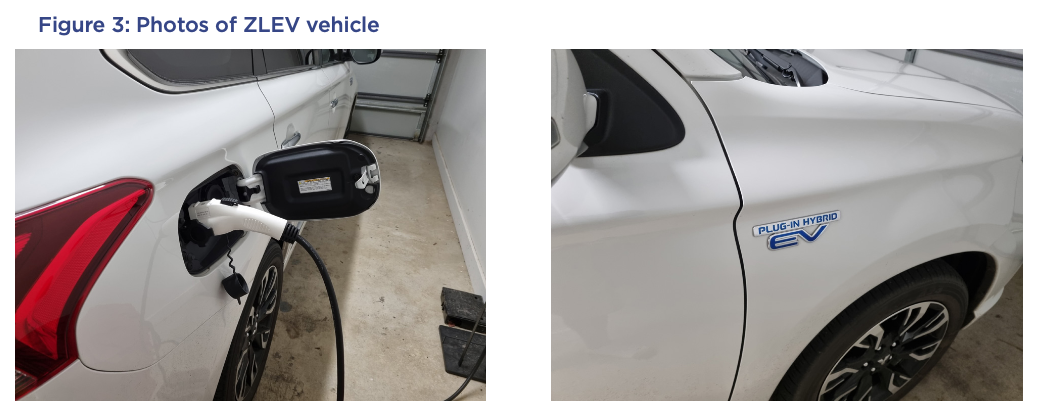

Case study 5 – Facilitating a hybrid vehicle registration discount

Anil purchased a hybrid plug-in car. When it came time for Anil to pay his annual registration, he was perplexed at the size of the fee. Anil investigated and discovered he was not entitled to the Zero and Low Emissions Vehicle (‘ZLEV’) discount because VicRoads did not deem his vehicle to be a ZLEV.

Despite his car not being registered as a ZLEV, VicRoads required Anil to provide an annual odometer declaration and to pay a road user surcharge which is only required for ZLEV vehicles.

When Anil contacted VicRoads, he was told that his vehicle was not a ZLEV and he should contact a generic VicRoads email address if he wished to pursue the matter further.

Anil emailed his enquiry to the generic address as directed but never received a response. Anil then reached out to the Ombudsman.

Either my car is a ZLEV in which case I should be entitled to the discounted registration, or my car isn’t a ZLEV and I shouldn’t have to pay the road charge.

Anil

After the Ombudsman made enquiries with VicRoads, it was established that Anil’s vehicle was not originally registered as a ZLEV because the car dealership that sold Anil his car provided VicRoads with incorrect information.

Given the new information, VicRoads confirmed Anil’s vehicle was in fact a ZLEV and he was entitled to the annual registration discount.

VicRoads also agreed to refund Anil’s previous registration payments to reflect the discount.

What can we learn:

Authorities should think about their internal processes when reviewing complaints. While many large departments have a number of areas or teams, complainants can become frustrated if they have to contact a different area about their complaint. In the VicRoads case, fostering a receptive culture and empowering complaint handlers to deal with issues up front could have led to an earlier investigation into the problem. This case illustrates that taking responsibility to resolve a complaint, rather than passing it on, can result in faster outcomes. The case was eventually resolved informally following our enquiries.

Considering the financial implications

We often receive complaints about payments, fees and fines. If an action or decision has caused a complainant to be unfairly out of pocket, authorities should remedy this with a refund or payment. In some cases, authorities have a discretion to waive fees or fines.

Authorities should consider an individual’s circumstances when assessing the most appropriate remedy to a complaint. Authorities also need to consider the impact of their decisions. The impact of a decision about fees or fines on someone who is in financial hardship will be different from someone who is not.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic we saw a number of authorities provide concessions or delay payments to support people in financial hardship. Our 2021 Investigation into how local councils respond to ratepayers in financial hardship found there is no single definition for ‘financial hardship’. This investigation identified the importance of authorities having a clear and accessible hardship policy containing a variety of relief options.

Authorities may also have the discretion to provide a payment to someone who applies for a grant or concession after a due date. When an authority intends to issue refunds or reimburse costs it is important that this be communicated clearly and that payments are processed promptly.

Case study 6 – Review finds unpaid physio bills for accident victim

Following a road accident some years ago, Kurt’s rehabilitation included regular physiotherapy.

Historically, the Transport Accident Commission (‘TAC’) covered Kurt’s physiotherapy, but Kurt was worried to learn that the TAC had suddenly stopped paying for his physiotherapy appointments.

In an effort to resolve the situation, Kurt reached out to the Victorian Ombudsman for assistance.

Ombudsman enquiries confirmed the TAC’s position.

However, the TAC reviewed the situation and found that it had inadvertently failed to pay six previous invoices and had underpaid an additional one.

Kurt was happy to learn that he had money owing to him and was grateful the error was corrected.

What can we learn:

Sometimes we resolve complaints in unexpected ways. We independently assess if an authority is permitted under the law to make the decision it made, and if the decision is reasonable. In this case, the decision was reasonable. But the TAC found an error with reimbursements for prior appointments. The complainant was satisfied he had a clear answer about his payments. Despite this not being the answer he was hoping for, he was pleasantly surprised that the TAC found the error and that he would receive reimbursements which could go towards future physiotherapy. This case highlights the importance of looking beyond the specific subject of the complaint and seeing problems which may otherwise may have been overlooked.

Case study 7 – New homeowners incur levy without notice

Max and Caitlin were looking for a place to enjoy their retirement. They finally settled on their home, that was part of a new estate. They moved in and soon felt very much a part of the community.

Ten months later the couple were contacted by their Council asking them to pay the Community Infrastructure Levy (‘CIL’), amounting to $1,150.

The CIL is typically paid by the developer or builder in a new estate and is a contribution to community facilities. The Council suggested the building surveyor had forgotten to check the CIL was paid before issuing the occupancy permit. The Council said because the CIL 'runs with the land', as current owners, Max and Caitlin were obligated to pay.

Max and Caitlin had several concerns about the process. They were also concerned that the Council failed to include the CIL debt in the Land Information Certificate in the contract of sale. They decided to complain to the Ombudsman.

We are at a loss as to what to do – this has come completely out of the blue and we feel we need some time to seek advice. We bought this house without any knowledge of covenants. We are both shocked and angry with the real estate agent and conveyancer.

Max & Caitlin

The Ombudsman made enquiries to see if the matter could be resolved fairly. After productive dialogue, the Council agreed to waive the CIL for Max and Caitlin - and 13 other property owners in the same situation. In total, the Council waived almost $15,000.

The Council also made changes to their processes to ensure a CIL is paid before occupancy permits are issued, to prevent this happening again.

Case study 8 – Student denied degree due to unpaid fees

Delighted to have finished her degree at a University in Melbourne, Li was surprised when her fee statement arrived with a figure higher than she was expecting.

The extra fees were for an additional unit of study Li had taken following a misunderstanding about which courses were mandatory for her degree. Li told us the University had advised her which courses to take; however, the University said they could find no record of this advice. Li decided not to pay the outstanding fees while she felt the matter was in dispute.

Due to the unpaid fees, Li was unable to graduate. This caused her stress as her student visa was nearing expiration and she wanted to apply for further study and extend her visa.

Complicating matters, Li’s home country had fallen into serious financial crisis, meaning that if she had to draw money from her home country to pay the additional fees, the real cost to her would be almost double the initial amount billed.

Prompted by the Ombudsman, the University confirmed the unit of study Li was charged for was indeed mandatory. As such, there was no doubt Li would need to pay for the course in order to graduate.

Li accepted this when it was explained to her.

However, the University had not acknowledged or addressed their delay in responding to Li’s initial complaint. A total of seven months had passed since Li made the original complaint.

After further enquiries from the Ombudsman’s office, the University decided to reduce Li’s outstanding fees by 50 per cent on compassionate grounds and in recognition of the impact of the significant delay.

What can we learn:

Complaints can provide a learning opportunity for authorities. Embracing complaints as free feedback from the community can help authorities identify where changes or improvements are needed.

While forwarding unpaid property fees to the current homeowner in this instance may have appeared to be a straightforward approach, this Council case demonstrates the importance of considering fairness. If a deficient process results in fees not being paid by the appropriate party, it is unreasonable to hold someone else responsible. In this case, the Council did well to review its processes.

Authorities should also consider if a decision or action has a financial impact on the complainant. In the University case, while the complainant was always required to pay the fees, the delay in explaining the reasons created additional financial issues for her. With our intervention, the University was able to exercise its discretion and offer a reduction to the fees on compassionate grounds.

Reflecting on the fairness of decisions

When responding to complaints, it is important for an authority to take the time and reflect on its decisions and the outcomes. Just because a decision was made under a particular policy does not mean the decision was fair, or indeed that the policy was fair. While most authorities have internal policies and procedures to guide staff, they should be encouraged and empowered to apply discretion to resolve complaints where appropriate. We often ask questions about how a decision was reached. We might ask how policies, procedures or legislation were applied or whether any alternative options were considered.

Authorities might also exercise discretion when the circumstances around the complaint are unusual or not fully within the individual’s control, remembering that not all complaints are the same. Reflecting on a complaint and its resolution can help authorities appropriately respond. It can also address broader issues, preventing similar complaints in the future.

Authorities may decide to acknowledge a mistake or clarify what they are doing to remedy an individual complaint. Addressing a gap within a policy or providing additional staff training can also resolve a complaint.

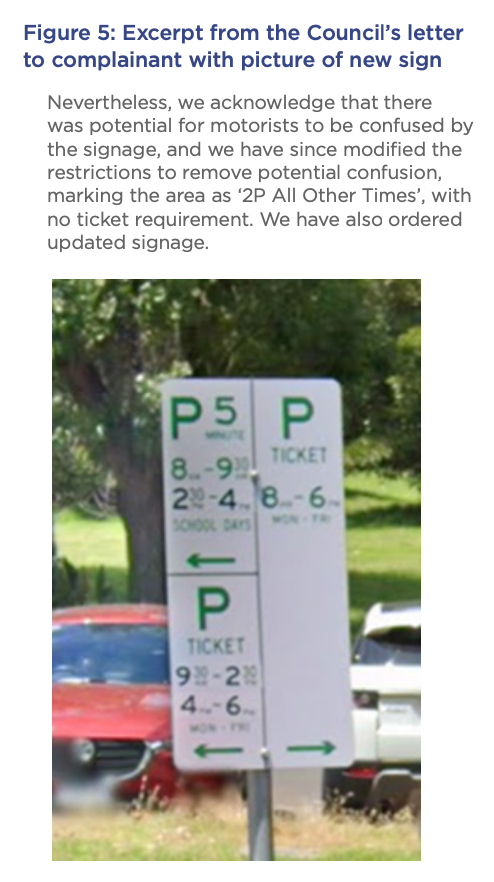

Case study 9 – Misunderstood sign leads to parking fine

Helene purchased an all-day parking ticket that ran from 9am to 6pm from a local Council. When she returned to her car at the end of the day, Helene found a fine for parking in a 5-minute zone at 3:30pm.

Helene paid the fine, as she was nervous it would escalate, but soon decided she would appeal the decision.

They fined me when I paid for parking and was doing the right thing.

Helene

Discussions between Helene and the Council revealed that the parking spot became a 5-minute parking zone from 2:30pm until 4:00pm, due to the nearby school. As such, the Council upheld its decision.

Helene complained to the Ombudsman because she felt the parking sign was confusing and the Council’s fine was unfair.

In response to our enquiries, the Council acknowledged the confusing nature of the signage and said it would update it. As a gesture of goodwill, the Council also offered to withdraw Helene’s infringement and refund the payment.

Helene appreciated the Council’s change of heart and believed the new signage would avoid future confusion for motorists.

Case study 10 – Dignity denied in prison search

When in prison, Emma was required to undergo a strip search and urine test while she was menstruating. The experience left Emma feeling embarrassed and she contacted the Ombudsman to complain.

Emma told us she felt embarrassed because the strip search was conducted without her having the opportunity to first clean herself and change her sanitary product. Emma was also concerned her urine test result may have been affected by the presence of menstrual blood.

I tried to say something at the time, but the officers said this was the procedure and I would have to do it this way.

Emma

After meeting with the General Manager of the prison, Ombudsman officers confirmed that while Emma’s urine sample would not have been affected by the presence of any blood, the prison needed to improve its policy and training to remind of the need for people’s dignity in this situation and responsibilities under the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic).

The prison has since engaged with Corrections Victoria to develop new policy and training. The prison was also asked to apologise to Emma for the way the test was conducted, which it did.

What can we learn:

Both these case studies show that authorities can informally resolve complaints by changing their policies or messaging. They are also examples of complaints that help an authority identify an issue which may generate future complaints.

Situations can arise which are not covered by existing policies. The prison case study shows the need to assess individual circumstances to ensure fairness. The prison recognised that changes to policy and staff training would support both prisoners and the staff they engage with.

While the Council did not make a mistake in the other case example, it acknowledged the sign caused some confusion and resulted in an unfair outcome for the complainant. The remedy offered in the Council case was two-fold, with the Council waiving the complainant’s fine and making the parking ticket requirements clearer for the community.

Case study 11 – Finger-pointing about a swamp in front yard

After stepping outside to get her mail one day, Billie was shocked to see her lawn looking like a swamp. Billie investigated and found water coming from a drain further up her street.

Billie first called the Council who, after a visit from a local roads inspector, stated it was likely the water company’s pipe that was leaking.

Billie next contacted the water company who insisted the issue lay with the Council.

Over the course of five months, Billie felt trapped in a stalemate, unable to get either party to accept responsibility for the issue. Eventually, Billie complained to the Ombudsman.

We have requested they attend to a leaking pipe which has caused my property to become swampy. We have made numerous complaints, the Council keep stating that it is the water authority’s problem, and the water authority says it is Council. I am asthmatic and now with the swamp area the mosquitoes are breeding rapidly.

Billie

Following our enquiries, the Council spoke with the water company, who acknowledged its pipes were the cause of the leak. Within five days, the water company excavated the area and conducted repairs.

What we can learn:

We are often approached by people who have been referred back and forth between two authorities who each claim the other is responsible for an issue. Where responsibility is disputed, a more proactive response from authorities could quickly resolve the issue. It is better practice for the authorities to reach an agreement between themselves and communicate the steps being taken, rather than leaving it to the complainant to resolve.

Case study 12 – Small business struggling for support

Pavel’s business was affected by COVID-19 lockdowns and he applied for a grant through the Licensed Hospitality Venue Fund. It took some time for the (then) Department of Jobs Precincts and Regions to assess his application, partly because of discrepancies in his business registration details. For almost 10 weeks, while Pavel’s business was not operating, the Department did not contact him about his application. Ultimately Pavel closed the doors to his business for good.

Pavel’s grant application was denied as his business was no longer operating when Business Victoria assessed it. The Department’s delay was not the only cause of Pavel’s business closure.

Pavel complained to the Ombudsman, telling us he had no choice but to close his business due to the significant financial hardship he was experiencing as a result of COVID-19 restrictions. He argued he would not have had to close his business if his application had been processed in a timely manner and he had received the financial support that the grant was designed to provide.

The Ombudsman made enquiries with the Department which initially said the $3,500 grant would not have been enough to allow Pavel to keep his business open.

However, the original grant of $3,500 was not the only funding available. Eligible businesses received subsequent top-up payments amounting to more than $30,500. We noted that that amount of money would certainly have had a greater impact on Pavel’s ability to keep his business afloat.

In response, the Department agreed to approve the original grant plus the top-up payments Pavel’s business would have been eligible for, equating to more than $30,500. While Pavel was not in a position to reopen the business, the grant money helped cover a number of unpaid debts that arose while his business was not operating.

Case study 13 – Victim of identity theft overrun with fines

Benita was confused about why she was repeatedly receiving fines relating to a vehicle she did not recognise. Eventually seven infringement notices were issued to Benita for incidents she had no involvement in.

Benita initially dismissed it as human error, but then suspected her driver’s licence details had been stolen after she had exchanged them with another motorist following a crash some months earlier.

Benita tried to resolve the problem for more than 18 months. She provided statutory declarations for six of the seven infringements. As a result, Victoria Police withdrew those fines. Benita unknowingly did not include the seventh infringement in the statutory declarations and it was passed on to Fines Victoria.

Feeling deflated, Benita paid the $574 infringement notice in June 2022 and lost three demerit points. However, trying one last time to rectify the error, Benita called the Victorian Ombudsman.

We asked Fines Victoria what considerations were made in Benita’s case and whether she could provide additional information to support her claim that she was a victim of identity theft.

Fines Victoria does not make decisions about withdrawing infringements but liaised with the issuing agency, in this instance the Victoria Police, who withdrew the infringement and ensured that the attached demerit points were also withdrawn.

What we can learn:

While not all decisions that are reconsidered by an authority will be changed, there are times where reassessment results in a different outcome. The Business Victoria case shows the impact of an authority not applying discretion and how this decision can further compound a difficult situation. While the decision was reconsidered, more timely processing of the application could have changed the outcome for the complainant’s business.

Dealing with complaints informally by asking questions and providing information in a different way can result in authorities reconsidering the complaint. While Fines Victoria was not in a position to decide on the merits of the fine, this case shows that authorities need to assist complainants with complicated review processes. The legislation around infringements can be seen as rigid, and late penalty fees can escalate quickly. It is important for authorities to recognise that considering the circumstances around complaints can result in fairer outcomes.

Resolving complaints through conciliation

The Ombudsman’s new powers to resolve complaints using conciliation allow us to get parties together to find solutions in a supported and structured setting. Conciliations are held in private and conducted with agreed, respectful rules of engagement. Our complaints officers are trained to detect where conciliation may be a sound option to resolve a complaint. Participation is voluntary for all parties.

Conciliation may be the best option if the complaint involves:

- an ongoing relationship between the authority and the complainant

- a breakdown in communication between parties

- a complex or long running dispute

- a problem that will be fixed by both parties taking responsibility

- multiple complaints about the same issues

- the opportunity to ‘humanise’ the bureaucracy and improve decision making

- acknowledgement of a poor experience

- an initial lack of shared understanding

- parties with a resolution mindset.

We ask authorities and complainants to prepare for conciliation by thinking about the steps that might resolve the complaint. It is important to bring an open mind and being prepared to listen.

Our conciliators help the parties to discuss the complaint. They evaluate everyone’s position and suggest options to resolve the complaint. Under the guidance of our conciliators, conciliation can:

- give parties an opportunity to explain what has happened and what they think is a fair outcome

- enlighten and allow parties to appreciate each other’s viewpoints

- empower authorities and complainants and lead to more meaningful and more sustainable outcomes

- achieve a speedy resolution for a simple or complex complaint.

In some cases, conciliation does not lead to a tangible ‘outcome’ for the parties. In these cases, we may:

- close the complaint

- make further enquiries

- conduct or resume an investigation.

The following case studies highlight the humanising effect that conciliation can have on a complaint. They highlight the power of bringing complainants and authorities together to generate a better understanding of each other’s perspective to ultimately develop a clear and shared path forward.

To protect the privacy of the conciliation process, in the main, the following case studies do not identify the parties. Where we do identify the parties, we have sought and received the parties’ permission.

Case study 14 – The Remembrance Parks Cemetery Trust

During the three decades since her passing, Bethany’s grave had been carefully adorned with personal mementos by her son Samuel. The items included a trophy and ribbons of Bethany’s football team.

Samuel and his family visited Bethany’s grave whenever they had the chance; it was a special place that helped Samuel keep the memory of his mother.

On one visit, Samuel discovered the personal mementoes by his mother’s grave had been removed – without any warning or reasons. He was shocked and saddened.

Samuel asked for answers from the Remembrance Parks Cemetery Trust responsible for maintaining the site, but became frustrated when they didn’t respond to him.

When Samuel complained to the Ombudsman, we contacted the Trust to learn what had happened. The Trust responded that it was deeply sorry for its actions. The Trust had commenced an internal investigation into how the situation had occurred and detailed the steps being taken to ensure it did not happen again.

Encouraged by the Ombudsman, Samuel and the Trust agreed to participate in an Ombudsman-led conciliation.

During the conciliation, Samuel told the Trust its actions had caused him deep distress and that the lack of answers from the Trust had also been incredibly difficult.

The Trust apologised to Samuel for his experience and acknowledged the distress it had caused. The Trust thanked Samuel for his courage coming forward to talk about his experience.

The Trust acknowledged its failures in answering him and explained that its staff had been overwhelmed at the time. The Trust detailed the comprehensive steps it was taking to ensure Samuel’s experience would never be repeated.

The Trust asked Samuel whether a representative of his family would participate in its community engagement about the problem and Samuel agreed.

After hearing the Trust’s apology and its commitment to improve communication and engage with the community about what had happened, Samuel felt acknowledged and said the Trust’s response had resolved his concerns.

Samuel told us that conciliation was what he needed, as his concerns had been acknowledged by the Trust, it had apologised to him and had taken ownership of the problem.

Conciliation with local councils

We often work with local councils and members of the public to resolve complaints through conciliation. Conciliation works well in these cases because the parties have an ongoing relationship and issues are often long running. Resolving complaints with councils in a lasting way sometimes requires both parties to commit to taking action well into the future.

Case study 15 – A storm water drainage issue

Vanessa had a problem with drainage on her property. She could not connect storm water pipes from her property to the Council-owned storm water drainage system. The Council incorrectly told her that the storm water pipes connecting to her property were privately owned, and she incurred costs investigating the problem.

Frustrated with the information she received from the Council, Vanessa approached the Victorian Ombudsman. The parties agreed to attend a conciliation. With the conciliators’ guidance, the Council agreed to connect Vanessa’s private pipes to the Council drain at their cost.

After the works were complete, the Council even agreed to restore Vanessa’s backyard to its original condition.

Following conciliation, Vanessa’s complaint was resolved, and she can now enjoy a functioning drain on her property.

Case study 16 – Noise complaints

We brought Milan and his local Council together over a noise complaint arising from Milan’s neighbour’s heat pump. The Council had been out a few times over a twelve-month period and given a warning to the neighbour. Milan completed a noise diary as requested by the Council, but he believed the neighbour should have been fined.

During the conciliation the Council committed to:

- attending Milan’s house, including at night, to assess the noise from his neighbour’s heater

- requesting Milan’s neighbour turn on the heating unit if it is not on when they attend to ensure the assessment can be carried out

- issuing infringements and considering prosecution if both of the above occur and the noise is assessed as ‘unreasonable’ and occurring during ‘prohibited times’

- engaging with Milan’s neighbour about installing noise cancelling material.

I don’t believe my complaint could have been handled any better

Milan

Case study 17 – Rates hardship

We assisted Lin and her Council negotiate a hardship arrangement for unpaid rates. Lin had a significant debt with her Council for unpaid rates due to her experience of family violence including financial abuse. Lin had sought an appropriate hardship arrangement but felt she would never be in a position to pay the debt to the Council. Lin was also worried that her Council would take legal action against her.

During the conciliation with the Council, the Council committed to:

- waiving $1,500 of the total outstanding rates and charges due to exceptional and severe financial circumstances

- keeping the current repayment arrangement in place unless there is significant change in circumstances

- not pursuing legal action in relation to Lin’s property provided she continued to engage with Council regarding any outstanding rates or charges.

[The conciliators][r]emained neutral and offered good suggestions to reach an outcome acceptable to both parties.

Council

Case study 18 – Drainage problems

We helped Reginald resolve an issue with a dam overflowing onto his rural property. The overflow was caused three years earlier when his Council conducted works, which changed the flow of water in the area. The Council had tried to rectify the issue a number of times, but it had not resolved things for Reginald.

During the conciliation between Reginald and the Council, the Council committed to:

- carrying out additional rectification work

- inspecting the whole length of the road alongside Reginald’s property

- cleaning out all drains and assessing whether additional open drains could be dug

- providing regular updates to Reginald

- developing a policy that guides storm water reuse by residents

- considering a claim for compensation.

I am very thankful that my complaint was listened to with sensitivity and understanding

Reginald

Conclusion

The Victorian Ombudsman’s office often helps complainants and authorities work together. Informal resolutions, including conciliations, are the ideal way to remedy complaints without the need for time-consuming and costly investigations. In each case where we conduct enquiries and conciliations, we ensure outcomes to complaints are fair and reasonable in the circumstances.

Each complaint to an authority is different and should be treated on its own merits. Where possible, discretion should be used to provide solutions which appropriately address and resolve a meritorious complaint. There should be clear, timely and transparent communication allowing people to understand why decisions were made. Fixing the problem that caused a complaint is one solution, but it is also important to address systemic issues so the same complaints don’t reoccur.

Dealing with complaints informally helps the complainant and authority alike. Complaints are free feedback which authorities can use to improve the way things are done. Authorities should regularly reflect on how they handle complaints and on how they can improve their complaint handling practices.